The air in the control room was a lie. It tasted of nothing, smelled of nothing, and hummed at a precise 22 degrees Celsius, a climate-controlled perfection designed to eliminate variables.

Dr. Aris Thorne considered it the purest air she had ever breathed. Here, in the sterile heart of her state-of-the-art, isolated research facility, she could finally breathe freely.

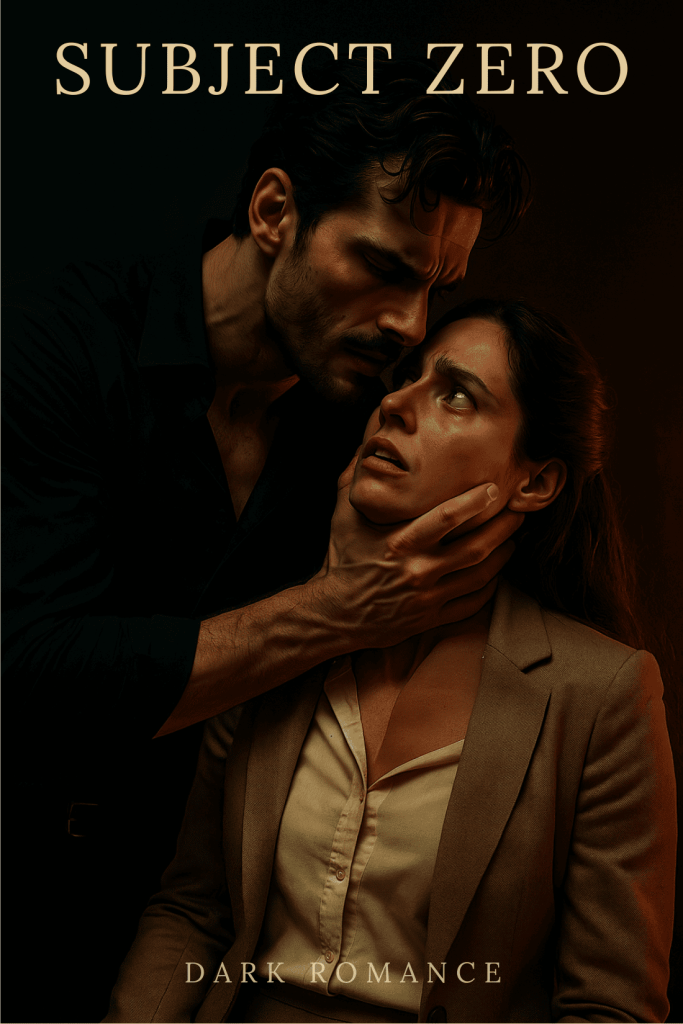

Her reflection stared back from the polished black surface of a dormant monitor: a woman rendered in sharp, efficient lines.

Hair pulled back in a severe knot, dark-rimmed glasses perched on a nose that was perpetually pointed down at data, and a mouth set in a line of determined neutrality.

Her white lab coat was a uniform, an armor. It smelled of antiseptic and ambition.

This facility, a sleek concrete and glass box buried deep in a private timber reserve, was the culmination of six years of relentless work.

It was her magnum opus, the crucible in which she would forge the final, unassailable proof for her doctoral thesis: The Pathogenesis of Obsessive Fixation: A Behavioral and Neurological Study.

Most of her peers were content with analyzing case files from a distance. Aris believed in immersion.

To understand the predator, you had to build the perfect cage and watch it from inches away.

And she had found the perfect predator.